Travel

Text and Photography by Mallika Chandra.

Chef Sanjana Patel, Creative Director and Executive Chef at the Mumbai-based La Folie, on an exploratory sourcing trip in Karnataka.

Earlier this April, Chef Sanjana Patel added me to a WhatsApp group named “Mysore trip”. “Hey everyone. Super excited to take you guys to Mysore for the harvest — nothing better than having friends over.” Friends. I smiled to myself. It had been a week since I finished working with her Mumbai-based patisserie and craft chocolate brand, La Folie, and it was during that conversation that she had invited me to accompany her on an exploratory sourcing trip to Karnataka. “No work!” she had said; she just wanted me to experience a cacao harvest. We had indeed eased into a newfound friendship from being consultant-client.

A few days later, I’m sitting in the backseat of a rental car, between Sanjana and her husband and business partner Parthesh Patel. In the front are food photographer Assad Dadan and our driver, Jai. Coming off an early flight to Bengaluru, we are now driving to a village called Hura, ahead of Mysuru. We’re rather chatty after a much-needed filter kaapi. I ask the couple how they met. “Actually, I’ve known Parthesh since before I truly fell in love with chocolate. That was when I went to boarding school in Ooty and spent all my pocket money at a local sweet shop called Mohan Agencies. Those almond bars!” I’m surprised at how little I know about her origin story, but also at how unexpectedly relaxed she is. My first impression of Sanjana had been that she was too serious for someone who makes chocolate for a living. But today, she is revealing a new persona. As if reading my thoughts, she laughs, “You’re going to see a very different side of me on this trip. I’m a lot more fun when I’m visiting cacao farms.” She continues after a pause, “I only wish I could do it more often. Whether La Folie exists or not, this is something I will keep doing.”

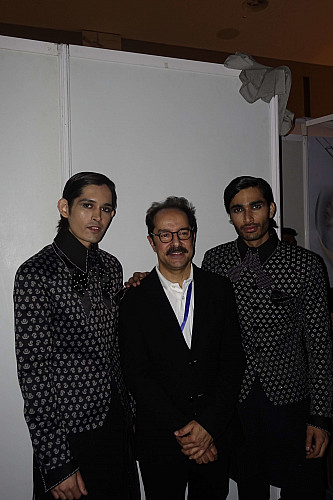

Thirty-seven-year-old Sanjana is the Creative Director and Executive Chef at La Folie. After training in Paris and working with global heavyweights, she brought her exposure back home and launched the brand in 2014. First came a millennial-pink dessert bar in the Kala Ghoda art district, followed by an experimental cafe, La Folie Lab, in Bandra (now closed), serving fresh breads, viennoiserie and light fare in addition to her signature desserts. At a time when consumers weren’t yet demanding it, she was sourcing quality natural ingredients and putting them on display. However, maintaining quality often meant importing ingredients, which wasn’t environmentally sustainable. “If I was talking about making recipes à la maison [at home], then why was I not focusing on ways in which we could become more hyperlocal?”

A leg injury in 2017 allowed her to pivot. “Most people recognised La Folie for desserts, but for me specifically, it was always about being chocolate-forward. And so I revisited the concept of making my own craft chocolate. I think that for any entrepreneur who’s been focussed on something for way too long, you kind of lose track and need to dial back a little bit.” Her pursuit to offer a “different sensorial journey and taste” to the Indian consumer ultimately “had to be tied to the very source [of chocolate]”: cacao. But what set her apart was using that craft chocolate not just in bars but also across other La Folie products. Today, Sanjana sources organic single-origin cacao from fair-trade cooperatives in India and abroad. Following a tailor-made bean-to-bar process, the chocolate is handcrafted in small batches at her factory in Mahalaxmi, Mumbai.

We stop at a highway snack shop to stretch our legs, and I press her on. Her research started in Tamil Nadu, near the Pollachi area where her father had once owned land. He connected her to a few cacao growers, but they were supplying only to industrial chocolate makers and didn’t understand the slow fermentation processes that ensure even fermentation as opposed to heap fermentation that is favoured by industrial chocolate makers, who add flavour via dairy and sugar. “It was very hard for me, as a woman, to explain or set up any system because they were very resistant. Back then I don’t think they saw cacao as being very valuable. They didn’t even know it was called cacao. They called it ‘Cadbury tree’.” This moniker is telling of the crop’s colonial history in India: first introduced by the British in 1798 and then built to scale by Cadbury (now Mondelez) in the mid 1960s. It isn’t hard to imagine, then, that there was a disconnect — both scientific and spiritual — between Indian farmers and this foreign plant.

Cacao is usually intercropped with coconut trees in the southern parts of India.

Determined, Sanjana strategised to use her time off to learn more about processing and understanding what wasn’t being done in India as she continued to try and work with the farmers. Still on crutches, she travelled to Central and South America with husband in tow, ultimately tying up with Uncommon Cacao, a group that sourced directly from smallholder organic farmers in Belize and Guatemala (they source from many more origins today and are a certified B Corp) and then processed the cacao. This placed Sanjana where cacao was first discovered by the ancient Mayans — its true origins. She also purchased beans from Ecuador, Peru and the Dominican Republic to diversify her brand’s palate. That trip cemented an affinity towards the cooperative model that she believed could benefit a large number of farmers on one end and oversee quality control for chocolatiers, like herself, on the other.

Things finally fell into place when she connected with GoGround Beans and Spices, a cacao fermentary set up by an Italian foundation in the Idukki Hills, Kerala. Idukki is the name of the district, but I notice that Sanjana always refers to the local village and taluka name: Udumbannoor in Thodupuzha — she is particular like that. “They had already created a post-harvesting fermentation and drying process. The founders Ellen [Taerwe] and Luca [Beltrami] knew a lot about cacao. They knew quality and were directly trading with the local farmers…even training them how to harvest, for example.”

Like with coffee, the flavour of bean-to-bar speciality cacao is developed during the fermentation processes of the beans.

We are now driving past lush coconut and banana plantations, and I ask her why she doesn’t talk about this journey more often. Sanjana makes a pained expression and confesses that it isn’t easy for her to open up. “I can do this with you in person, one-on-one, but the moment I have to talk about myself online, and market it, I get anxious. Even putting up one Instagram story to document this trip today is overwhelming for me, but I know at some point I have to do it.” Creative founders like Sanjana are pressured into lending their brands an “authentic” personality and actively differentiating their products using inventive jargon to survive in the loud landscape of social media marketing. “You know, technically, even a Nestlé or a Cadbury is making bean-to-bar chocolate. Bean-to-bar is just a process. What you create with the chocolate is a craft. Craft chocolate is clean chocolate; there is nothing else to it. So I keep focusing on that. And that has to start at the level of the farmer.”

After a quick lunch in Mysuru, we reach our farmstay that is conveniently located near the cacao estate we plan to visit. Sanjana truly feels at home in this part of the country. I wonder, out loud, if she wishes she had her father’s farm to grow cacao herself, “Today, I see it as a bane to own the land because I will get stuck at only farming. While it’s great to be able to say it’s grown in-house, the chef in me wants to, more than anything else, do something with the working cacao farmers in our country.” She adds that GoGround’s willingness to experiment with fermentation most aligned with her own experimental nature as a chef. “That’s why many chocolate brands have won awards with GoGround’s beans. Consistency is required, but consistency doesn’t need to be literal. At the end of the day, you’re working with a crop, soil and food. There are variables, but that allows me to expand a flavour profile and explore further through roasting, conching or pairing with different ingredients.” Sanjana explains how flavour varies across Indian cacao origins — Kerala is closest to the equator and hence produces acidic, sharp and tart flavour notes, while beans from Tamil Nadu are creamier and nutty. Karnataka’s are on the spicier end, and they have milder fragrant and floral notes, more tropical like soursop and litchi. For her, this journey may start at the farm but always ends at flavour.

The flavour varies across Indian cacao origins based on the terroir and intercropped species. For Sanjana Patel, this journey may start at the farm but it always ends at the flavour.

Left to right: Soursop fruit; Cacao flowers; The inside of the cacao beans revealing fermented cocoa mass.

Dadan, who has accompanied Sanjana on earlier sourcing trips to GoGround, joins our conversation. Together, they recall ploughing through barely drivable dirt roads in the Malabar forest to look at cacao trees. They wonder how difficult it must have been for Taerwe and Beltrami to raise their two sons there. I question whether two white Europeans really deserve such praise, given the power dynamics in this context, but neither Dadan nor Sanjana shares my misgivings. “I spoke to a lot of farmers there, and they genuinely had very good things to say about GoGround. They aren’t encroaching on the land itself, which I like. They are paying fair-trade prices directly to the farmer, whether it is 5 kilograms of beans or 10 kilograms. Everything about this trade is based on trust. They were there helping those farmers when the floods came in 2018. Even now, they’re not going through a very good season, but they’re trying their best to keep their farmers and buyers happy, which I appreciate.” It gives me insight into what Sanjana is really searching for on a sourcing trip like this.

Why look for another source then, I enquire. “Frankly speaking, there’s a dearth of cacao in this country…. At the same time, I hear close to 80 per cent of the beans in Karnataka are going to waste,” Sanjana points out. The problem is multifold — climate change is affecting cacao yields and farmers are cutting their trees or contracting out to industrial players. She reveals that she has been approaching farmers in Karnataka and Andhra Pradesh throughout the pandemic. The most promising lead has been Chempotty Estate, a 22-acre plot of land that’s been operating as certified organic fruit and cacao farm for 20 years. The owners — a corporate professional and a retired teacher — follow “spiritual farming” in reverence to nature and only use Jeevamrut as a natural fertiliser. Besides, the fact that they began growing cacao only six years ago and are just starting to supply to local buyers offered an exciting opportunity to establish post-harvesting processes from an early stage.

Our arrival at Chempotty Estate; A glass of cacao juice.

We arrive at Chempotty Estate in good spirits. Thankachan Chempotty meets us at the gate. We follow him along an avenue of tall coconut trees, and I observe Sanjana walking ahead and noting the species layered in the understory — a mix of timber, fruit and medicinal trees. Under these, she points out the multicoloured cacao pods we seek. “It looks like the genetics of cacao here is varied,” she says quietly to me. “See that? Two different soils. Instantly, it tells me that there is going to be some inconsistency in the beans.” In the heart of the farm, Jessy Chempotty welcomes us with an infectious smile and a glass of fresh cacao juice. It tastes like litchi, and I instantly go in for seconds. Jessy calls it her daily glass of “happy hormones”. A lesser-known by-product, the juice flows out of the cacao pod when cut open, and this precious elixir is hard to bottle because it starts fermenting so quickly. The best place to enjoy it? A cacao farm!

Outside the Chempottys’ cottage, Dadan and Parthesh relax on hammocks while Sanjana and I settle down in the verandah opposite our hosts. We look at some freshly picked cacao pods, and she points out the mix of varieties here as well. Chempotty admits that a lot of their saplings were given by CAMPCO (Central Arecanut and Cocoa Marketing and Processing Co-operative Limited) and Cadbury. It is a common occurrence in commodity-driven agriculture for large organisations to set up nurseries and distribute favourable varieties to farmers in the area, and cacao has been no exception. A major downside, however, is the loss of wild or heirloom varieties and indigenous knowledge as well as the introduction of hybrids that usually make the farmer dependent on industrial methods and inputs. Additionally, industrial buyers compromise on the quality of the beans because they compensate for flavour with dairy and sugar. For Sanjana, this portends inconsistent yields and requires more rigorous fermentation protocols. After looking at a batch of processed beans, she suggests they do a cut test. When both husband and wife peer inquiringly at her, she takes charge, transforming the verandah into a classroom.

“I hope you don’t mind, but I like to make it very clear from the start that if the quality is not up to the mark, then I will not be able to work with you,” she says. “But, of course, that means that I am here to break down the process for you and share all the knowledge I have because I’m very transparent, and I look for collaborators who are receptive to that. At the end of the day, I’m a chocolate maker, not a farmer. And you should not just blindly listen to me. Do the experiments and see for yourselves.” The tone is set. “My second expectation is for you to keep your trees healthy. It is a labour of love. We might be talking about inconsistent flavours or taste, but it does need consistent effort. I also understand that your expectation from us is that we’re going to ultimately buy this harvest from you.” I glance up at the Chempottys, and their only response is to pull out their notebooks. They welcome her candour.

Left to right: Cut test in the verandah; Setting expectations; Exchanging information with the Chempottys.

Sanjana has obviously done this before. She asks the couple to pull out a sample of 50 beans and demonstrates how she wants them cut lengthwise. As they get to work, she sorts the cut beans into groups based on their fermentation and evaluates which are acceptable. A cut test, she explains, is a tool to visualise what is happening inside the beans during fermentation and drying — it is where the flavour develops at the farm. “The goal here is to achieve consistency, and that comes from setting up SOPs [standard operating procedures].” Parthesh joins us with his laptop and presents some of the post-harvesting processes set up by their partner cooperatives. “Internationally, what’s nice is that there are grants given, communities built and platforms created for cacao farmers. It is more organised and structured…. I don’t think we have that.” Sanjana chimes in. “There is no solid government effort to protect the craftsmen and artisans in our country when it comes to food. There are beautiful concepts out there, but they’re done privately, and I really cherish chefs who are getting out of the kitchen and sourcing at a grass-roots level.” They don’t withhold any information, offering alternatives more suitable to the farm’s operation scale and local weather.

While Sanjana and the Chempottys remain immersed in technical discussions, Parthesh, Dadan and I are led by four workers into the plantation to observe the harvest. The roles are gendered. Men harvest pods using an improvised sickle with a very long handle. Women follow swiftly, putting the fallen pods into bags. We don’t speak a common language, but they kindly caution us against the fiery red ants crawling all over. That explains the long handles! Sanjana joins us and advises that the pods be collected under shade and not in direct sunlight. It is nice to see Chempotty nudge his workers to join the conversation and participate in the knowledge exchange. Bending over, Sanjana points out inconsistencies; some of the pods are already too dry while others are unripe. She explains that measuring the Brix, the dissolved sugar content, will indicate when a pod is ready. Sugar means flavour. Further, each varietal would require its own harvest protocol. I am surprised (a recurring feeling this trip) by her knowledge outside of the kitchen, clearly built over years spent understanding how farming practices affect the beans. Her approach is both artistic and scientific. When it comes to cacao, specific chemical reactions find equal footing with sensorial notes or nostalgic memories in discussions; they are always the protagonists in her story.

The harvesting of cacao followed by a soulful lunch cooked by Jessy Chempotty.

Jessy calls us for lunch in the verandah. We are joined by Patricia Cosma, a professional craft-chocolate taster and co-founder of the upcoming Indian Cacao & Craft Chocolate Festival at the Bangalore International Centre, Bengaluru. She is the common link. Sanjana helps Jessy finish off some foraged greens on an open fire and the rest of us lay out banana leaves on the table. Jessy’s home-made pickles and relishes act as the perfect accompaniments to our soulful meal — a simple vegetable curry, sautéed greens and red rice.

After lunch, we head to another part of the farm to remove beans from the pods harvested earlier today. Again, tasks are divided — men cut open the pods while women sort the beans. Sanjana observes their method for a few minutes and then gets right into it. An immediate cause of concern is the black pod disease, consistent across South India and caused by a fungus. Diseased pods need to be separated first because missing this step makes sorting difficult at a later stage. She begins to sift through a basket of pulpy beans and tosses those that show signs of germination, or are too dry or overripe. The workers pick up her cues fairly quickly. Maybe it is the physicality of this exercise, but Chempotty and Sanjana are able to prototype a potential working relationship. It’s a give-and-take, where she sets standards and he evaluates their worth. The next logical step, they agree, is to ferment a small batch, for which she improvises an anaerobic setup. Guiding Chempotty and his workers, she meticulously goes over each step and the reason behind it, including what to expect and monitor over the next 24–48 hours.

Observing how beans are sorted; Sharing methodologies; Doing a fermentation experiment.

At sunset, we walk back through the coconut grove to the verandah, making good on our promise to have Jessy’s payasam. Spontaneously, Sanjana pulls out some of her favourite craft chocolate bars. Cosma then guides us through a tasting; the most sensorial and rounded experience, we learn, comes from consuming chocolate at room temperature and letting it melt on the tongue. “Instantly makes you slow down, doesn’t it?” The conversation shifts to a more existential note when the Chempottys admit that committing to craft chocolate standards has been difficult. Sanjana empathises. “I question myself as well. I think it just comes down to the value that you put onto a piece of chocolate. It’s a very difficult business to be in,” she says. In retail, they contend with huge listing fees for shelf space, 95 per cent of which is still occupied by industrial chocolate and imported brands. “I think culturally, at some level, we have lost value for what is home-grown. Maybe because we’ve grown up eating that chocolate, that nostalgia is there. Or maybe we’ve always heard that Belgian or Swiss chocolate is the best. Even our wines and cheeses are top-notch. But there’s just no value for it because it doesn’t taste like a particular Fontina in Italy, for example. Of course it’s going to be different! It’s artisanal.”

Left to right: Payasam; A chocolate tasting.

We’re back the next morning to check on the fermentation experiment, and all is looking good so far. The last item on our agenda is to taste some of Jessy’s experiments with cacao outside of chocolate; an ongoing interest of hers is to avoid wastage of the farm’s produce through creative recipes and preservation. We taste a cacao vinegar akin to balsamic, a darker cacao dip like molasses and, even though it is probably too early for it, a glass of cacao wine. My favourites are her cacao nib jam and cacao laddoos sweetened with jaggery. We marvel at the potential of this fruit that many people still don’t know is the source of chocolate, and I sense a newfound sorority between Sanjana and Jessy.

Jessy Chempotty’s experiments with cacao outside of chocolate.

Top (left to right): A line-up of fermented drinks; Cacao vinegar.

Bottom (left to right): Cacao nib jam; Cacao laddoos.

I catch up with Sanjana a few weeks later and she tells me, “I actually got that batch of beans. The fermentation was good but the beans were over-dried, so we weren’t able to use it.” Encouraged by the Chempottys’ efforts in trying some of the techniques discussed, she is planning a longer visit to get a microlot fermentation done and to involve other farmers, to make the exercise more community-driven. “Mr Chempotty has been very forthcoming. For a farmer to process cacao is another challenge. And once they tell themselves that they have values like staying organic at the bare minimum, maintaining fair and ethical trade and wages, and ensuring consistency in quality of the fermentation, then they want to stay committed. The next thing they may ask is, ‘Why don’t I just make my own chocolate?’ And I say yes, of course they can!”