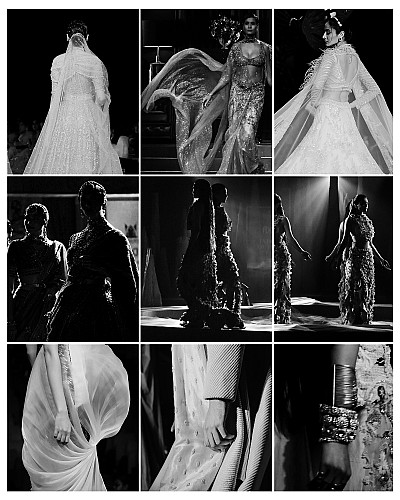

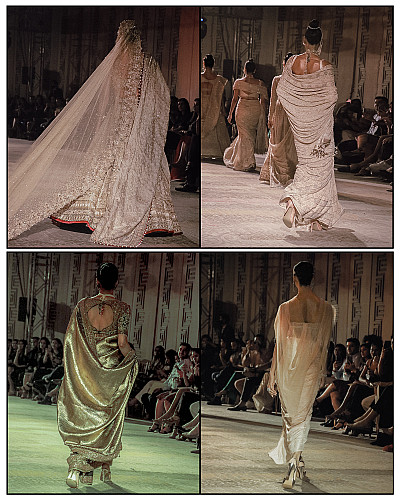

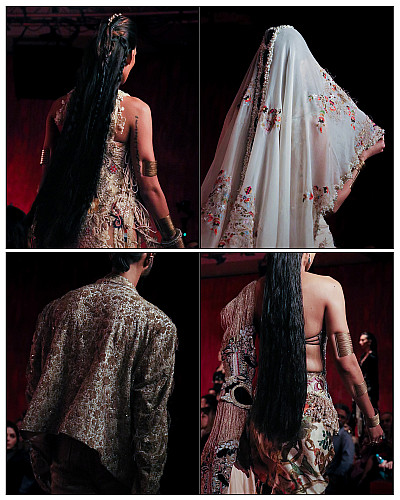

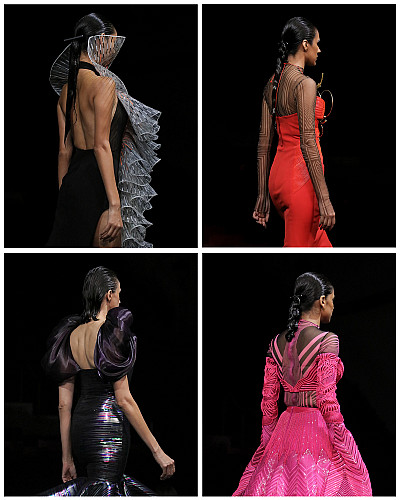

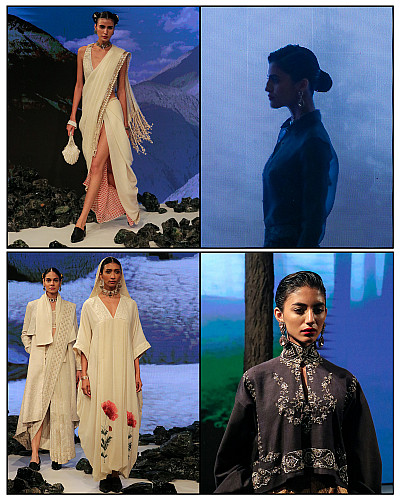

Moderation and Photography by Asad Sheikh. All images from FDCI India Couture Week 2022.

Top row (left to right): Falguni Shane Peacock, Dolly J, Suneet Varma

Middle row (left to right): JJ Valaya and Anamika Khanna

Bottom row (left to right): Amit Aggarwal, Kunal Rawal, Anamika Khanna.

Asad Sheikh (AS): Can everyone please introduce themselves?

Tanay Arora (TA): I’m a textile design graduate and currently employed as a design consultant by Srishti Trust for Aranya Naturals, an organisation that works with natural dyes, shibori and eco-printing techniques, and Athulya Paper Studio.

Anmol Venkatesh (AV): I recently graduated from NIFT [National Institute of Fashion], Delhi, and I work as an assistant designer at Péro.

Yash Patil (YP): I’m a fashion designer, currently working on custom design projects on a freelance basis.

Somya Lochan (SL): I have been exploring different crafts clusters for the past one year, and right now I am working with Raw Mango as a textile designer.

AS: Let’s discuss our understanding of couture in the Indian sense.

YP: I think, Asad, we could start with you. What is your understanding of it?

AS: Couture in India is seen as occasion wear, primarily based on the market it caters to, and also the price point. The Indian bridal wear market is one of the most lucrative segments of our fashion economy, and multiple designers have geared their collections around that. My understanding is that Parisian couture, its most famous global counterpart, is more geared towards selling fantasies, whereas Indian couture has a very commercial element to it in terms of brand strategies, which dilutes this aspect.

YP: It’s more of a bridal week here; many of the pieces that get made are focused on catering to a certain occasion. We don’t see a lot of explorations in terms of silhouettes that you would expect from a couture week. Globally, brands have been building their individual images around the idea and exclusivity that they present at Couture Week. But here in India, there are common silhouettes that run through different brands. There are only slight tweaks as far as the themes they refer to.

AV: Creatively speaking, that is the biggest factor for the Indian market. It’s so intertwined with the bridal- and occasion-wear market. That in itself comes with certain baggage and aesthetic templates that designers have to adhere to, right?

YP: It’s also about the clientele and what they are opting for.

Tarun Tahiliani

AV: Yes, because couture is a heavy investment from the designer’s side. Look at the pieces they put out there — the craftsmanship required to create that is not cheap.

SL: But I also feel that couture — its handmade, hand-designed, custom-made aspect in particular — is not new to us. This is what India stands for, and it’s just that the term is Western. Simply speaking, this age-old practice is now being reintroduced after the coinage of the term, just like with sustainability. But we can’t ignore the fact that this is something we have always done and are simply building on it.

TA: India has been synonymous with stunning craftsmanship communities for generations. The idea of the design process in a capitalistic sense — that it’s controlled by an organisation or a person — is still relatively new here. Most of the brands that are presenting are controlled by the designer that founded them.

YP: As Somya said, pieces would be made in every household and passed down from one generation to another. The whole idea of the personal touch to a piece that we call couture — where we say that it passes through so many hands — was always there, and on a more personal level. I think it was more detailed and now we have certain houses that work with a certain style. And that’s only presented to the market. So there’s not a lot of, umm…

TA: Diversity?

YP: Each segment, city and state has certain crafts, textiles and styles that were showcased earlier, but, now, it has been made homogenous, and a certain silhouette passes around from the top to the bottom of our country, which really wasn’t the case before, right?

TA: Also, a lot of the work that’s currently being shown is very similar in the form of techniques, and there are very few brands that are branching away from that. For instance, everybody’s doing aari work — the way it’s being done differs from brand to brand, but the base techniques are very similar.

Rahul Mishra

AV: It boils down to the kind of representation we have. The designers all come from specific contexts, and they cater to that same saturated market. As someone who comes from southern India, I see very little representation of where I come from in the Fashion Weeks, and I can say the same for other parts of the country as well. So even when we speak of the kind of expertise that’s being showcased, it’s very tied to the context it is coming from.

YP: There’s also the use of textiles. Historically, every state would use their own textiles as a base to produce a certain garment. We call it Couture Week, but the lehngas aren’t made out of Indian textiles. Designers rely mostly on mill-made fabrics. They use a lot of nets and tulles. For fabrics, we look to the outside world, and for embroideries, we look inside the country. The result is something that is not very Indian.

TA: But I think it’s important to highlight that the consumer base they’re catering to has been consuming Western content at increasing levels for a while now. Brands need to be able to sustain themselves commercially in order to bring about a change in the consumer pattern in some way. In the post-pandemic market, it’s important for brands to make profit.

SL: The consumer base is a very important factor. I was having this conversation with Sanjay [Garg] just two days ago, and he told me how a time came when women only wanted to look slimmer, taller, and fairer. Supply caters to demand, and that’s how this template came to be. And overall, because people started prioritising wider trends over their cultural heritage.

AS: Firstly, I think we all can agree that if couture is loosely defined by how difficult or unreasonable it is to produce a piece on a ready-to-wear mass scale, then the artisans are at the centre of it. And, for the longest time in India, a lot of the textile, sari weaves and motifs represented community storytelling, and there was a distinct sense of individualism that arrived from that. However, now we see brands making an effort to fit into a certain framework. Having said that, I think some designers have really started to explore how to make their designs look more individualistic while sticking to textural textile work because in India, couture happens on a textural level.

Amit Aggarwal

TA: We work a lot with textiles and embroideries, so the bulk of our work for Couture Week should be looked at through not just the silhouettes but also the textural work the designers use. I feel like Rahul Mishra and Amit Aggarwal have been able to capitalise on a classic silhouette and a particular technique in a way that’s not been done by others. When you look at a Rahul Mishra garment, the 3D embroidery that he does with the aari work is very classic to his label. Understanding how to capitalise on having a signature silhouette or style that people can easily identify but that also differentiates you from the market is important.

AS: And I think that’s where a lot of Western couture differs from its Indian counterparts. In the West, many designers have historically capitalised on a set silhouette and style of embroideries. When you think of Chanel, you think of feathers and tweed and bejewelled embroideries. Whereas in India, our base form of innovation is at the textile level. So then how do you hypothetically say “Okay, I own chikankari”? No one designer owns a particular kind of craft or style associated with it. How they play with it to create a sense of individualism is perhaps how they can move forward with it.

TA: It’s important that nobody ever tries to own a craft because it’s a generational practice. So you can use it in a new way, or in a way that’s very original to you, but at the very same time, the craft will exist on its own, and other people are always going to use it.

SL: In fact, Yash and I have found ourselves in this discussion so many times where we have concluded that we can never set a timeline or give ownership of a craft to anyone, because how do you track what the original craft was? And how it evolved from there.

AV: You can’t control the number of people who are practising these techniques.

SL: At any point in time, there are ten people saying, “I’m going to change this craft.” Take a technique like chikankari. There’s someone who may come and say that they will do something new with it, and the 300-rupee chikankari piece is now valued at 600 rupees. Then someone else adds something new to it and so on. And then comes a stage where you can’t correlate that piece to the original work. And then someone says, “Okay, let me take you back to where it was”, and suddenly the original form of the craft is selling for, say, 3,000 rupees. It’s a cycle, which will keep running on and on.

TA: I find rebooting to be a recurring theme in Indian couture and fashion. I think we have a trend cycle where we tend to go back to the original work, which makes me hopeful.

Anamika Khanna

AV: That’s very true, but it’s still relegated to specific crafts. In India, some craft sectors are very organised — I’ve worked with quite a few of them — and there are others that are completely unorganised. So, when it comes to the Indian couture scene, we do repeatedly work with set crafts. And when we are talking about crafts surviving in this ecosystem, we are very specifically talking about these particular crafts that already have a kind of star power. It’s also important to recognise that Indian couture’s obsession with royal worldbuilding is very intertwined with the crafts that they choose to work with. I think, in that regard, we have to also look at the idea of just what Indian couture in itself is and who fits into it.

SL: India has never been about silhouette-driven design. We are very good with textiles, and that is how it has always been. If you go to the Calico Museum of Textiles in Ahmedabad, you will see how silhouettes were introduced into the market. The boxy silhouettes that we see and appreciate so much, those are basically the result of errors. Textiles and couture cannot be separated in India. Secondly, artisans and couture, again, work in sync — design houses need artisans, artisans need design houses.

AS: If I may introduce a point here — Indian couture, and the designers working within that framework, are working to sell the garment they’re showing. It has to reach a customer, while in the Western sense of approaching couture, the garment may or may not necessarily reach a customer because the cost of designing could be underwritten by the licensing the brand might do via, say, a perfume line.

TA: It’s really important to note how many Western luxury fashion brands have been able to make themselves financially accessible to some degree. For instance, Chanel No. 5 made the brand accessible to a wider audience who cannot afford to purchase the garments that Chanel sells. No major Indian brand has done that yet by capitalising on their regional status as a couture house. Even though we’ve historically been such an important part of the spice trade and fragrances have been so essential to the Indian wardrobe for generations. We’ve been manufacturing attar in Kannauj in Uttar Pradesh for centuries. But fragrances have not been introduced by any major Indian couture house. And I do think that it’s a very interesting space that they could explore, to make themselves accessible to the general Indian audience.

Amit Aggarwal

YP: What you mean is that Indian couture has to be a lot more exploratory in terms of not just design and inspiration but also a broader commercial strategy, right?

TA: That would give designers some degree of creative freedom as well. If Sabyasachi, whose bridal wear is so well known, were to come out with a perfume tomorrow, that could definitely bolster the brand, and it might create a template for others to follow. It could help designers make the more experimental or untested designs that they want to because the cost of producing a couture piece in India is very high in local currency. Ultimately, the aim is to manufacture and sell it here.

SL: We cannot ignore the fact that India is a developing country with a capitalist economy, which is still growing. So introducing experimentation or creating fantasies for that matter is a complete challenge here.

AS: Design and market elements of couture aside, I think one important point that we haven’t covered yet is how it is like working with the artisans after the pandemic.

SL: It’s two-sided. On the one hand, places like Rajasthan and Gujarat have boomed, with everyone going to Rajasthan and wanting to get their things made in Kutch and Ahmedabad. On the other hand, I come from Ranchi, Jharkhand, and I see how the artisans are struggling; they are changing professions and abandoning looms. Villages with looms are now filled with vacant houses.

TA: I worked with the craft clusters in Bhagalpur in Bihar during the pandemic and it was a similar story to what is happening in Jharkhand. They were not able to manufacture anything. Gujarat has been doing a lot of manufacturing for a while, so they have a network built in to get them back up — the pandemic has had a very diverse impact on different parts.

AV: Recently, I spent time at a few sari-weaving clusters in Karnataka and Tamil Nadu, and I found that the artisans have had to make a living through other means because their looms were simply not running. But I noticed that specifically with embroidery artisans, it works on two levels. Either you’re part of a couture house or you’re under an independent contractor who supplies employers and you work piece by piece.

YP: Outsourcing it. Yeah.

Anamika Khanna

AV: And it was a massive hit for the artisans working under contractors when the market shut down because they didn’t have an employer who was answerable to them.

SL: Yash, we recently discussed how the middleman culture has come back.

YP: Yeah…it definitely has.

AS: Could you elaborate on that because my understanding was that the middleman culture is shifting and becoming less prominent?

SL: So many of us were working consciously towards getting artisans back into the business. Yash and I have discussed creating a directory to contact artisans directly. Suddenly, there’s a boom for middlemen because people can’t travel but they need their textiles. One person leads to another and then another and so on, and that’s how you can order a textile. But the artisan gets very little, and there is no way to track it. It’s so difficult to reach the artisans directly now, and it’s been a big setback in the textile industry.

YP: The same situation is prevalent within the sector that does embroidery for brands outside of India as well. A lot of brands in Europe, for instance, outsource all of their embroidery work to vendors who are in India. I was in touch with a few of these spaces, and even here, it was very lacking. When artisans had to go back home to their villages, they didn’t return, so a lot of the time, the vendors also suffered.

AS: Design houses must have faced disruptions while working with the artisans, especially when it came to maintaining their pre-pandemic standard. The entire network has shifted.

SL: As a woman working on side projects where I was required to actually be part of the clusters in villages with no washrooms, I found it difficult. This might come off as my little sob story, but working for days on end in a remote location that’s replete with patriarchy is not easy. The men there are not accustomed to listening to a woman. The closest store is four or five kilometres away. These kinds of challenges make you reconsider an easier solution. I could get someone in Delhi to do it. Maybe it’s going to be a machine-made piece but then again, people go by the aesthetic and visual value, and are ready to consume it.I think Tanay would completely understand where I am coming from.

TA: Very few people would want to do that.

SL: And in the end, it’s all about the fact that your audience is okay with what’s being provided to them. We are not ready to accept and acknowledge good fashion.

TA: Plus, we’re living in a very visual world right now, where you’re constantly bombarded with visual communication thanks to social media. If you see the same silhouettes and textiles repeatedly, you start to associate them with high fashion appeal.

Anju Modi

AV: But then again, when we talk about how so many designers show the same silhouettes, we have to understand the people buying these clothes are not just the brides or the younger, more “experimental” woman, so to speak. These decisions are influenced by other family members, like their mothers, in-laws, grandparents and so on. The individual is not in complete control over their purchase. Because in India, we do keep external factors like society and family in mind when we make these massive purchases, especially clothes catering to social events. And the designers have to work and run their businesses within this framework.

AS: On a concluding note, where do you see Indian fashion and couture heading? I think our fashion scene really kicked off in the 1990s. So we are much younger as an industry that designs and sells.

YP: I think we are still at a place where we are finding and exploring a language. Couture Week has only been around for 15 years.

TA: I hope that the field — by which I mean the organised structure of a professional fashion house, a concept that is still new to the Indian landscape — develops and comes to co-exist with the age-old crafts in the Indian landscape, without having to pigeonhole itself. I hope to see a broader clientele emerge in the future, one that buys garments that are manufactured in India for an Indian audience. And that these garments are not just bridal. It’s more than that.

AV: Perhaps I come from a bubble where people are more aware about fashion, but I’m optimistic about the kind of demands that consumers will eventually put forward as their base grows.

SV: There are young designers cropping up everywhere, and they are readily experimenting. And there are established ones who are opening up their horizons to newer things too. And this process is going to come together to generate multiple diverse languages.