[ad_1]

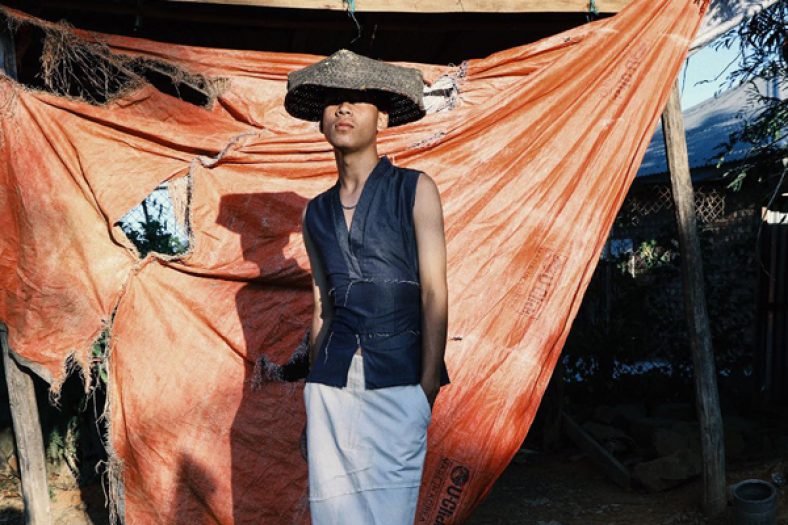

Interviews by Mallika Chandra. Photographs by Naomi Shah.

PARAG TANDEL

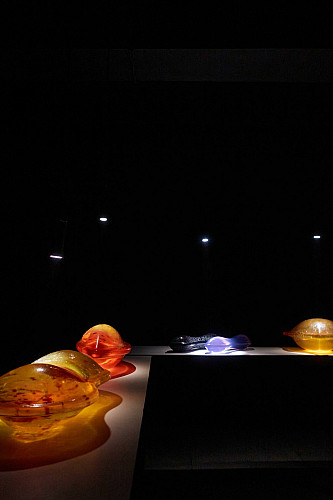

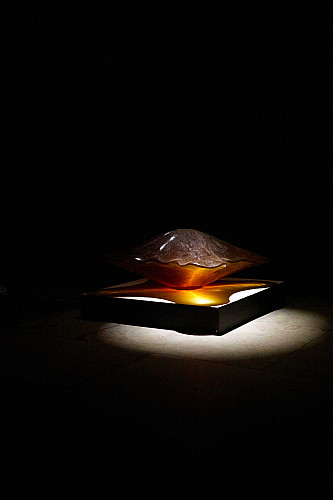

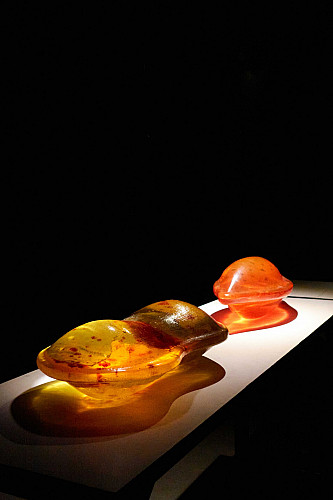

Vitamin Sea

Do you think that the festival provides visitors with an opportunity to engage meaningfully with the Koli fishing community and the issues that they face at large?

The festival at Sassoon Docks acts as a site-specific artistic intervention. I create socially engaged art and it’s how you mould people’s minds that is important. The city does not know much about the Kolis, I don’t think urban dwellers are concerned about our ongoing issues; they are busy earning their livelihoods and pursuing their ambitions. This festival is an attempt to redirect attention towards the issues plaguing the community.

What was your relationship with Sassoon Docks like in your growing-up years? And did showcasing your work here bring back any memories?

My mother was in the retail fish business for over 40 years and I used to accompany her to Sassoon Docks to buy fish. I have memories of walking around the area with her and imbibing life lessons of no-escaping-hard-work. Vitamin Sea is about food and sustenance. The Kolis worship marine life. The whale shark, for example, is locally known as Bairi Dev, and it survives on turtles — who we refer to as Kasav Dev — and planktons.

Was the material chosen from a conceptual as well as a stylistic point of view?

Resin is now part of our material culture. Earlier, our boats and large vessels were made out of jackfruit wood, but now most of our fishing vessels are made of FRP (fibre-reinforced polymer) resin which, I think, is an obvious material to use. I like the material’s rooted stillness. My indigenous identity is always reflected in my art practice. The resin I use is a transparent medium — it goes well with my aesthetics and way of seeing.

Can you walk us through your creative process?

I start by drawing. My sketchbooks are not the small A4-sized ones but much larger (7 feet by 5 feet) and mounted on an easel. I keep drawing in them. The exercise involves consistent engagement. Later, this drawing is transformed into a three-dimensional large-scale clay work, for which I use Shadu clay as it is local to Mumbai. I enjoy doing everything myself, I like to work with my hands for that’s what makes us humans. It’s a long process-based work in which the whole body is engaged.

AYAZ BASRAI

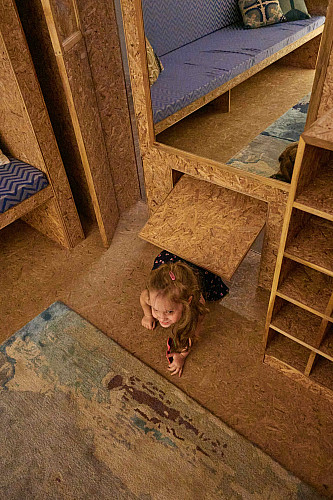

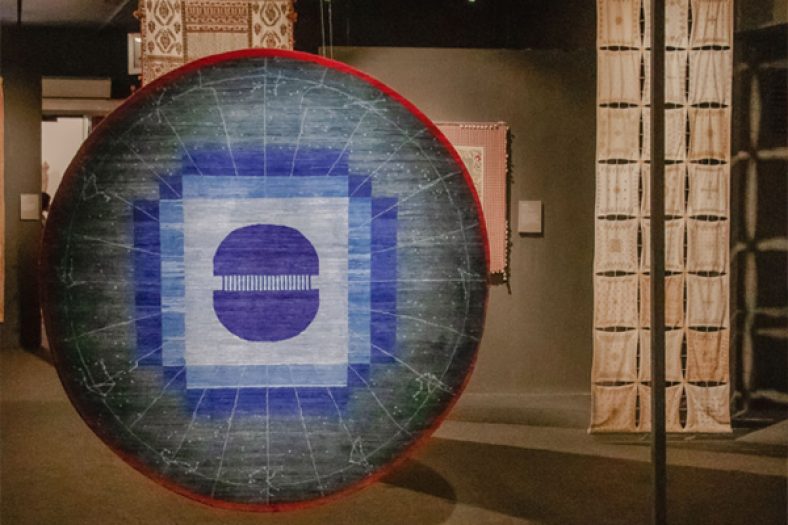

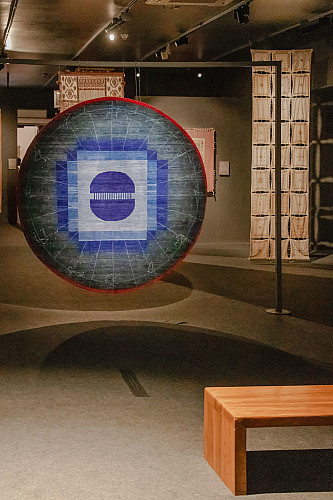

The Magic Cube

Your work is motivated by how living in compact spaces might look like in the future….

From our very first conversations with Hanif [Kureshi; co-founder and artistic director of St+art India Foundation] and his team, we started developing the idea of a micro-home fit-out, more as an idea prompt for visitors. The massive potential of a festival like this is that it becomes a marketplace for ideas. We respond, critique, parody and fall in love with our city all over again. Our installation was shrunk down to mirror the flats that we spend our lives in — the concrete boxes that are provided to us by builders to conduct our life, work and play in.

We do a great disservice to our homes when we take them for granted, allowing them to become static backdrops to our lives. Our homes have the potential to make us more aware of our surroundings, create active and vibrant lives and make us more engaged and curious about the world we live in. But only if we allow them to, and if we design them to enable this. Our work at Sassoon Docks was situated in a really lovely old bungalow, perfectly square in plan. We thought it’d be fun to insert a prompt around future living, a hyperfunctional cube that collapses the functionality of an entire home into itself. The idea was to introduce a prototype future home which, ideally, visitors could ponder over, critique, discuss and maybe build — their own versions, at their own homes.

Your work raises questions about the future of compact living spaces. Are you any closer to answering these?

The Magic Cube installation is actually part of a longer iterative set of experiments that we’ve been engaged in since 2006. My first home in Ranwar village in Bandra was also an exercise in hyperfunctionality. I lived for two years in a 160-square-foot “apartment”, with sliding walls and furniture that allowed me to have a walk-in wardrobe, a walk-in library, a full-size desk and also a king-size bed, just by moving a few walls on channels. The act of living in this sort of context, where I had to actively create the spaces I needed on an hourly basis, created a sort of choreography with furniture, and a very active relationship with the home. We then worked on another project titled Folly House that engaged in these inquiries through a 4,000-square-foot space that introduced ideas of craft and hypermobility into the mix. Zameer (my brother and co-founder of The Busride Design Studio) built hyperfunctional pieces into his own apartment in Bandra.

Watching visitors walk around the cube and then discovering different entry points into the space, discovering cat doors and secret cubbyholes, was really fun. And through social media we’re able to relive a bit of each visitor’s experience. I hope that there’s some resonance, and maybe a handful of them went back with ideas they’d like to explore in their own homes. I do believe that hyperfunctionality and intense design detailing exercises will create the sort of homes we’d like to live in, in future cities. Compaction culture affects all of us, irrespective of our demographic. Even the well-heeled in Mumbai live their lives out of concrete boxes, stacked one above the other in an increasingly concretised city, and prompts like these may create small cocoons of hyper-utility in spaces that desperately need hard-working solutions. Our homes must be at least as hard-working as us, if not more. This is not just a Mumbai thing, it’s true across various megalopolises; compaction culture is playing out in increasingly interesting ways. Compaction culture is endemic, and the city is its manifestation.

Were the materials chosen from a conceptual as well as a stylistic point of view?

Through a judicious choice of material, we hoped to create The Magic Cube as a diegetic prototype. A diegetic prototype is a tool used in speculative fiction, an area of design we’re very actively exploring currently. A diegetic prototype is a work in progress and its only role is to provoke dialogue. The idea is to not create a finished product that can be sold or marketed, but rather a rough-around-the edges scaffolding that users can flesh out with their own conceptions of what a home would look like for them individually. We chose to stay away from a finished idea, as well as excessive propping. We created almost the entire structure with a single material, oriented strand board (OSB), for its rough exposed visual texture. This is offset by a bunch of products, fabrics, wallpapers and fittings from Asian Paints, our event sponsor, to complete the trappings of a future home. In going down this road, we were able to build a certain open-endedness to the exploration and stay away from subjective and aesthetically derived responses that tend to take away from the inquiry.

Can you walk us through the process of creating the installation?

Our first step in creating the installation was a site visit with the St+art team, and a sort of free-ranging curatorial chat with Hanif, who is an old friend and long-time collaborator. We were very interested in exploring the idea of a future-home set within an old-home context, to spark the imagination of what life in a city could be like. The Asian Paints Art House also served as one of the event venues for the festival, so we had to keep in mind the basic movements of crowds. A gathering space was created on the ground floor for events, lectures, discussions, product launches and the NFT (non-fungible token) gallery. And Asian Paints also used it to announce the launch of their colour of the year. As we developed the design, we created a bunch of OSB samples exploring treatments and material juxtapositions, to better visualise final outcomes. Saee [Pagar] from our studio spearheaded the entire build and worked closely with Suresh [Vishwakarma] and his team of carpenters to design and execute the entire space. There was a fun interaction with the Asian Paints team as well, to integrate some of their home products into the space, to provide much-needed context and colour to the installation. Being a time-bound, deadline-based build, it was pretty much non-stop work with daily supervision to ensure it all came together on time. The highlight for me was how the finished object blurred the boundary between being a room and an object. It sort of behaved like an object in the Art House context, but a room when you actually engaged with it.

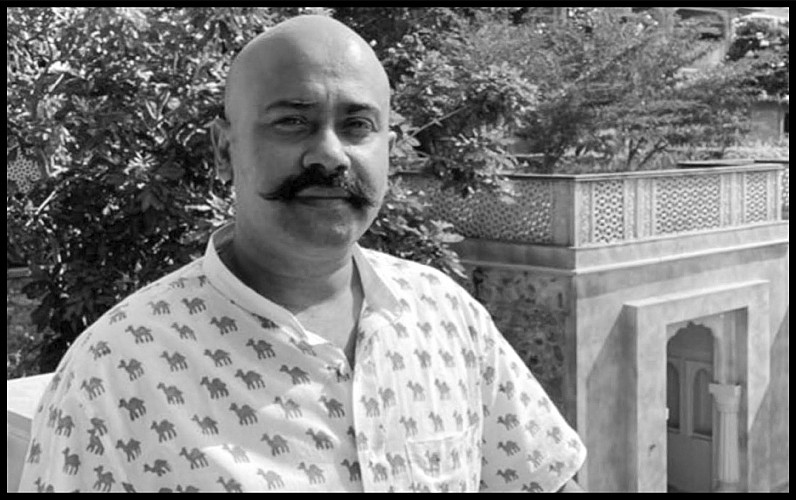

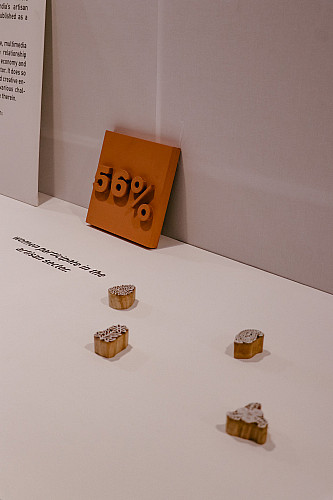

AMRIT PAL SINGH

Toy Faces

How do you think the concept of nostalgia responded to Sassoon Docks, the site of the installation?

Toy Faces is a collection of portraits that are driven by nostalgia and childlike wonder. Toys are objects reminiscent of an extraordinary time when the word “cynical” wasn’t part of our vocabulary. The collection celebrates individuals and characters through history and fictional stories, to remind us of our first sources of inspiration and revisit the feelings that come with experiencing complex worlds for the first time.

Over the last two years, I have created several Toy Faces, playing with signature bear ears, button eyes and Pinocchio noses with several characters and avatars on an open canvas.

In this exhibit, I have extended the Toy Faces NFT to five artists — Atia Sen, Neethi, Osheen Siva, Santanu Hazarika and Zero — taking inspiration from Silver Escapade, the Asian Paints Colour of The Year 2023. The result is a playful collaboration celebrating the spirit of our youth while incorporating various styles and mediums.

This is the first time that NFTs were a part of the Mumbai Urban Art Festival. How do you think the public has responded and engaged with them?

Digital art is one of the most widely used art mediums. NFTs and blockchain have disrupted this medium and allowed it to become tradable. I have received an incredible public response with numerous shares and messages in my social media inbox. By being part of this festival, Toy Faces has shown us the potential of this medium.

What was it like collaborating with the other artists for Toy Faces? Do you see more artists collaborating in the Web3 space in the future?

I agreed to participate in the festival mainly because of its collaborative nature. At first, I was anxious about extending my collection to artists from different mediums but it soon became apparent that this would be one of my best collaborations.

Web3 is an incredibly collaborative space; it’s common to work with fellow artists in Web3 and even collect art from them. Because of less institutional involvement in Web3, artists depend on each other more here than in traditional spaces. Plus, smart contracts and blockchain make the entire collaboration very transparent.

[ad_2]

Source link